In this line of work, one often has to find balance between the heaviness of need that exists in the world, the inspiration and motivation caused by the great work being done to address the need, and the recognition that this fight is not a new fight. At times it is both humbling and defeating. One way that I try to strike that balance between heaviness and inspiration is by trying to celebrate those that came before me that contributed to housing equity and community development work. Their work spans beyond the confines of a single month; nevertheless, as a part of our ongoing celebration of Black History and Black History Month, here are examples of two individuals that are not only worth celebrating, but worth remembering so that we may remain grounded and move forward.

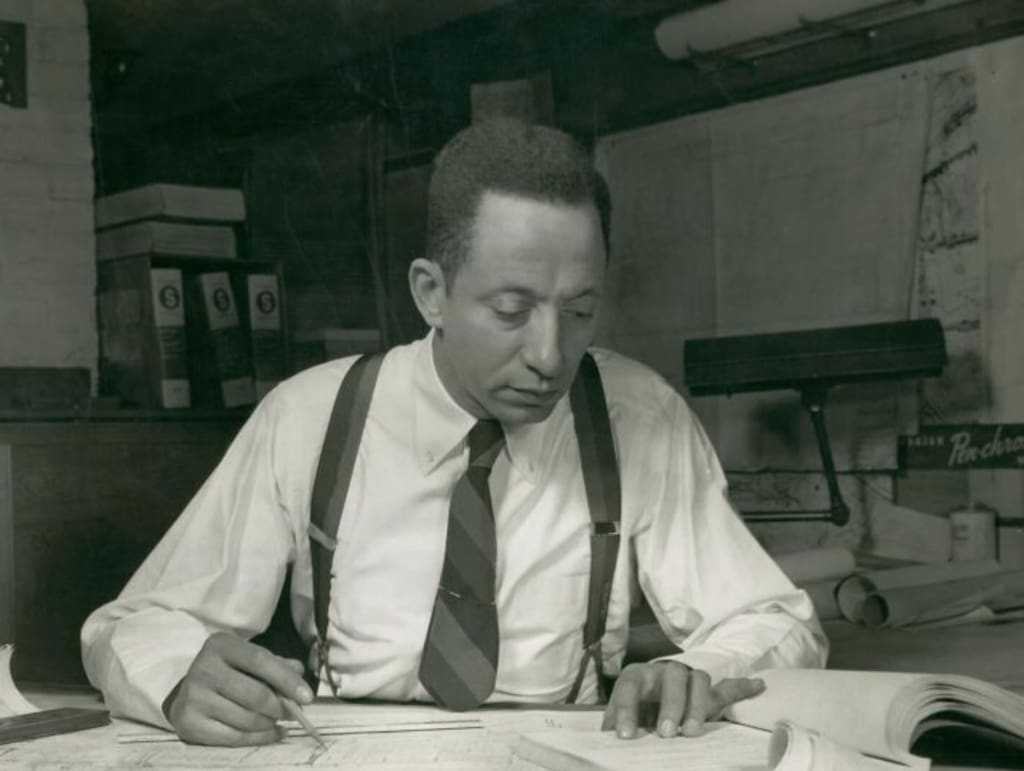

Mr. Hilyard Robinson (1899-1986) was a prominent Black Architect that dedicated his life to engaging people with intentionally designed spaces that represented his belief in the importance of space in advocating for equitable, safe, and diverse communities. He was born in 1899 in Washington D.C., attended and graduated from the prestigious M Street High School–the district’s first school for African Americans. He went on to graduate from Columbia University with an architecture degree in 1924 and worked for the federal government for several years.He was inspired by his time in the service during World War I and traveling in Europe where he witnessed mass housing efforts.

His work at the federal level led him to arguably one of his most famous designs, the Langston Terrace Dwellings, the first federally funded public housing development in D.C. Robinson’s design directly defied the standard aesthetic that tenements had in prior decades. Instead, he thoughtfully created 274 low-rise apartments and row houses that complemented the local landscape and included gathering spaces for residents as well as public art. It opened in 1938 and was one of eight different public housing developments that Robinson would design.

Dorothy Mae Richardson (1922-1991) was a dedicated community organizer and trailblazer in the field of community based development. She lived in the same community for over 45 years in Pittsburgh. Throughout the 1960s, Richardson organized several of her neighbors, creating an all resident, all women-led community group named Citizens Against Slum Housing (CASH) and lobbying city bankers and government officials for help improving their community. She believed in holding both landlords accountable for improving the conditions of their properties, and financial and government institutions accountable for the consequences of redlining by advocating for them to play an active role in community revitalization. CASH ultimately convinced 16 different financial institutions to give out conventional loans in her community, helping finance the rehab and preservation of many homes by securing a $1 million high-risk revolving loan. The resident-led group became Neighborhood Housing Services (NHS) of Pittsburgh in 1968.

Dorothy Mae Richardson is known as the founding mother of NeighborWorks America. In 1978, Congress institutionalized the NHS network, which had established the Neighborhood Reinvestment Corporation, which we know today as NeighborWorks America. The NeighborWorks America we know brings together over 400 community development organizations throughout the country. Her legacy is one that models navigating the role of a community-based leader and organizer while building and advocating for institutions that would serve the traditionally underserved and disenfranchised.

Stepping Back to Move Forward

When I dove into the stories of these two individuals, I wanted nothing more than to talk to them, to ask how they did it. I read over the issues they were passionate about – intentional design; creating spaces for community to gather together and live in an affordable, safe, and fulfilling way; investing in neighborhoods and communities historically disenfranchised; and organizing community members to meet the immediate needs of today while building better institutions for tomorrow. It is STILL all so relevant, and all so important.

We STILL have to advocate for affordable housing to be accessible, safe, and intentionally built spaces for individuals, families, and communities to thrive and grow.

We STILL have to counter the dated assumptions that people have about what affordable housing does and does not “look like,” when the affordability is largely grounded in the spreadsheet behind the development, not the aesthetic of the development itself.

We STILL have to advocate for resources and investments that are needed not only to counteract generations worth of disinvestment or other deconstructive policy decisions, but to also meet the true scale of the constantly rising need for affordable housing across our communities, our state, and our nation.

We STILL have to hold institutions and individual landlords accountable for the roles they play in facilitating access or barriers to affordable housing.

And while all of the above may be true, and may weigh heavy, let us remember the importance of taking a step back and celebrating people like Hilyard Robinson and Dorothy Mae Richardson for paving a way for our fight in the first place.